THE POSTGRADUATE SHORT ARTICLE

The subversive practices of reminiscence

theatre in Taiwan

Wan-Jung Wang*

Royal Holloway, University of London, UK

Founded in 1995, the Taiwanese Uhan Shii Theatre Group has created 12 distinctive reminiscence theatre productions and has performed locally in Taiwan as well as globally around the world. The company has developed its own theatrical aesthetics of memory, and their work not only represents the traditions of Taiwanese culture and habitus, but it also subverts its conventions. In this paper I will examine how the aesthetics of production represents Taiwanese cultural habitus and how their representation of female experience subverts orthodox cultural expectations and traditional gender roles associated with them.

The background and context of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

Taiwan has been ruled by different political regimes, undergoing colonisation by Japan and ‘re-colonisation’ by the Kuomingtang nationalists (shortened to KMT)1 immediately after the Japanese occupation in the twentieth century. Culturally and historically, Taiwan has been influenced by Chinese and Japanese imperialism as well as ‘modernised’ by Western neo-colonialism, and the hybrid culture of Taiwan indicates this post-coloniality. It was only after the lifting of Martial Law in 1987 that the Taiwanese began to reconstruct their own multiple histories and, as part of the process of decolonisation, started to renegotiate a more secure sense of their own identities. The Uhan Shii Theatre Group was founded in this emerging movement of cultural decolonisation in the 1990s.

The director of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group, Peng Ya-Ling, was an active theatre practitioner in the experimental theatre movement in Taiwan in the 1980s, where she adapted Western avant-garde theatre forms developed during the 1960s. Later, she went to London to attend the London School of Movement and Mime, and received rigorous training in Etienne Decroux’s form of corporeal mime. Although her performance was often praised by her British teacher as ‘uniquely Taiwanese’, she was unaware of this quality in her work at the time. When she returned to Taiwan in 1990s, she embarked upon a personal journey to seek her ‘uniquely Taiwanese’

*Department of Drama and Theatre, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey

TW20 0EX, UK. Email: w.c.wang@rhul.ac.uk

ISSN 1356-9783 (print)/ISSN 1470-112X (online)/06/010077-11

# 2006 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/13569780500437754

qualities. Her personal journey collided with a collective quest for cultural identity on

the island. By interviewing traditional performing artists and community-based

elders, she started to re-learn her own culture and traditions. These interviews

motivated the foundation of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group.

The Uhan Shii Theatre Group is the first Taiwanese theatre company exclusively

dedicated to the performance of the oral histories of community-based elders. By

recovering and performing their buried memories, the company reconstructs

Taiwanese historicised identity and, in the process, reaffirms it. The elder

performers, who had never before undergone any professional theatre training,

perform their life stories in collaboration with Peng Ya-Ling, the director. Reclaiming

a sense of their own post-colonial subjectivity is a shared goal for Uhan Shii’s director

and its elderly performers, who are differently marginalised according to gender,

ethnicity, and class groupings. In the following section, I will demonstrate how the

aesthetics of production presents and reclaims a specifically Taiwanese cultural

identity.

Aesthetics of production

Places are often inscribed by people’s memories and interpretations. Conversely,

people are also inscribed by the places in which they have dwelt. The interrelationship

between people and places is a process of inter-inscription and is constantly

changing according to people’s different needs at different times (Agnew et al. , 2003,

pp. 290297). Places are inscribed upon the elders’ bodies with cultural meanings

which derive from their social experiences. Pierre Bourdieu described the significance

of such physical imprints as ‘social habitus’, and sociologists Halbwachs and

Connerton have stressed the importance of the body in producing and reproducing

cultural remembrances (Halbwachs, 1950, pp. 7884; Bourdieu, 1977, pp. 7887;

Connerton, 1989, pp. 58, 88). This combination of the social and cultural practices

inscribed on the bodies might be described as a ‘cultural habitus’, a term I am using

to suggest the ways in which Taiwanese elders in the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

demonstrated their neglected and colonised cultures in performance.

On stage, the elders’ physical presence is visible to the audience as they tell their

stories and means that reminiscence theatre exhibits the historical sedimentation of

places upon bodies. In the Uhan Shii Theatre Group, Taiwanese cultural habitus is

presented by performative elements such as the elders’ dialect, singing, gestures,

postures and movement as well as the director’s mise en scene. The social habitus of

Taiwan is presented by the individual elders’ habitual gestures and postures which

derive from their social encounters in Taiwan.

The aesthetics of production evident in the company’s work reflects the influences

of the cultural habitus of Taiwan in two ways. One is concerned with looking for its

‘roots’ and the other is related to the ‘routes’ Taiwanese people have travelled and

their encounters with other cultures. Firstly, ‘looking for roots’ suggests the quest to

re-establish the subjectivity of the previously disfranchised and oppressed Taiwanese

people. The company deliberately recovers histories and languages of ethnic minority

groups such as Hakka and Holo who have been suppressed in the past, and those

from the currently marginalised ‘mainlander group’ in Taiwan.2 By performing

stories in their own dialects, these performers are offered the chance to restore

subjectivities that have been exploited by different dominating political regimes.

In 1995, the Uhan Shii Theatre Group started to devise a series of productions

called Echoes of Taiwan based upon the oral history accounts of Taiwanese

community-based elders. These productions established critical acclaim for their

theatrical reflection of Taiwanese cultural identities. In the production Echoes of

Taiwan III*/The Story of Taiwanese Men premiered in 1998, the Uhan Shii Theatre

Group demonstrates the cultural hybridity of Taiwanese men and women under

Japanese colonialism and KMT’s nationalism. The production also reflects the

influences of both Western and Chinese theatre cultures on the director Peng

Ya-Ling. This mirrors the two directions of Taiwanese cultural habitus: the roots, by

recovering histories hidden during the colonial and nationalist periods; and the

routes, by renovatingWestern and Chinese theatre cultures with a renewed vision. By

synchronising the influences of routes and roots, the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

reflects the complexity of contemporary Taiwanese culture.

In the first scene of Echoes III , the ritual of a Taiwanese man taking a bath

demonstrates the imprint of Japanese imperialism through a series of movements.

Portrayed by a retired merchant, Wu Wuen-Cheng, the man sits upright and

motionless with one arm straight up whilst his wife rubs his back silently. The

commanding and unyielding posture of the patriarchal man and the submissive

posture of a subservient and obedient wife reflect the imprint of Japanese colonialism

on Taiwanese culture. In contrast to the dominating position in his domestic life, in

public the Taiwanese man kneels down and bows in front of a Japanese soldier to ask

forgiveness for smuggling pork for his family. These two images mirror the complex

imprint of Japanese colonialism on elderly Taiwanese men. He both enacts Japanese

patriarchal postures at home and succumbs to an inferior position as the colonised in

public. By contrast, Taiwanese women are doubly oppressed by complying with both

colonialism and patriarchy and diminished into the role of silent submission. The

humiliation inscribed upon the wife is shown vividly in another scene when she serves

the tea respectfully for her husband and persistently extends her hand to ask money

from him, but in vain.

After Japanese colonialism, the KMT nationalists also left a legacy of suffering and

restraint on the Taiwanese people. That means that when the KMT nationalists

practised stringent political and military rule in Taiwan, they left physical imprints of

suppression on Taiwanese people. This point is demonstrated in the second part of

the Uhan Shii Theatre Group’s production of Echoes of Taiwan III . The character,

Tsai Yi-Shan’s father, was almost beaten to death in the period of ‘White Terror’

when the KMT crushed opposition to its police state. His crime was to ask KMT

soldiers to return his sheep which had been taken by force.3 Seeing his badly

wounded father, his mother’s creaking scream and cry resonates on stage. The image

of his mother wrapping his father haunted him for years and was made into an

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan 79

unforgettable stage picture (see Figure 1). Consecutively, the hushed gestures

exchanged between the two men crouching with their backs on small stools and their

image bound by the long white strips of cloth hanging from the ceiling, reflect the

physical and psychological restraints experienced under nationalist rule.

An alternative direction of Taiwanese cultural habitus is manifested in the

director’s travelling ‘routes’ from the West back to Taiwan. Through exploring

indigenous cultures, Peng Ya-Ling counter-balances the Westernisation and neocolonialism

that permeated the cultural scene of Taiwan in the 1980s. Furthermore,

her ‘unique Taiwanese’ quality is especially reflected in the hybridity of her acting

training and directing style. It is fused with indigenous Taiwanese theatre aesthetics,

Chinese traditional theatre concepts and Western experimental theatre forms.

Nevertheless, this hybridity reflected in her theatre works also contains a strong

awareness of the need to seek and sustain her own cultural subjectivity. This is a kind

of ‘critical hybridity’ rather than the ‘happy hybridity’ that Jacquelin Lo describes.4

Peng’s creative and critical synchronisation of artistic styles from different theatrical

traditions creates a new artistic style of her own. This is a distinctive example of the

hybridity of Taiwanese culture.

In her mise en scene, Peng Ya-Ling employs circular rather than linear blocking

which resonates with Chinese traditional theatre aesthetics.5 An example could be

drawn from ‘the lantern parade’ scene in which Taiwanese and Japanese children

circle the stage to parade their lanterns on the occasion of the Lantern Festival in

Figure 1. Echoes of Taiwan III*/The Story of Taiwanese Men in 1999, the scene demonstrates that

Tsai Yi-Shan recalls how he watched the sheep when he was a child as well as how his mother

wrapped up the wounds for his father, who is beaten by KMT nationalists at the far back of this

picture, as his life-long haunting image. Courtesy of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

Echoes of Taiwan III . In her choice of narrative strategy, she combines storytelling

directly addressed to the audience and lyrical singing that expresses the inner feelings

of a character. This is typical of the Chinese opera style, and is well-illustrated in the

soliloquies and Japanese singing in Echoes of Taiwan III . In the tender singing of

Japanese songs, the elderly man and woman express their ambivalent and suppressed

feelings towards Japanese colonial rule combined with love and hate, adoration and a

sense of inferiority. In the same production, the symbolic use of props such as stools

to represent sheep recalls the property usage in Chinese theatre. In a game-playing

scene, for example, Wu Wuen-Cheng and Tsai Yi-Shan play a game of throwing

cards while they talk about the restriction of Chinese education under Japanese

colonial rule. They pause at the point when they begin to throw their cards as they

are fixed by their time; they freeze the moment of play as a perpetual moment of their

childhood to highlight this memory. This tableau-like effect resonates with Chinese

opera’s ‘Liang Xiang’, which is a highly stylised movement in Peking Opera; when a

character first appears on stage, he or she will hold their characteristic posture and

gesture with a certain special tempo of music for a moment on stage in order to stress

their distinguishing characteristic.

The trademark of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group is the transformation of the

movements of daily life into stylised movements, thereby turning the ordinary into

the extraordinary. This derives from Chinese theatre aesthetics, in which daily

movements are deliberately stylised. The emphasis on physicalisation to reveal the

inner feelings comes from Ya-Ling’s meticulous training in the school of Etienne

Decroux in London. The best example of how this Western training has become

assimilated into her work is the scene of ‘pulling the white hair’ in Echoes of Taiwan

IV*/If You Had Called Me. The elders repeatedly pulling their white hair as a group

in slow motion symbolises the past that they wish to forget.

Peng Ya-Ling employs modern Western theatre aesthetics such as lighting, sound

effects and slide projection to create a ‘total’ theatre effect and to reinforce the

dramatic atmosphere. In the process of training the elders in acting, she has applied

Feldenkrais’ method to liberate the elders’ bodies from conditioned social bounds

and incorporated training in ‘psychodrama’ and ‘contact improvisation’ to unfix both

their physical and psychological blocks. In this collaborative process, Ya-Ling draws

upon improvisation techniques to develop scripts with the elders in the rehearsal.

The ritualistic slow motion movement, shown in the scene of ‘wrapping the wounded

father’ in Echoes of Taiwan III , derives from the non-realism style that Ya-Ling was

exposed to in the 1980s’ experimental theatre movement adapted from the West in

Taiwan.

Based upon the above examples, Uhan Shii’s aesthetics of production demonstrate

the cultural inter-inscription of roots and routes in Taiwan and reflect the on-going

process of Taiwanese identity formation. The performances also offer the opportunity

for a triple reflexivity upon histories from the performer, the director and the

audience. Their dialogues with their complex personal and cultural histories

continue to shape the new and ever-changing identity of Taiwan.

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan 81

Taiwanese female experience presents and subverts the symbolic power

and space

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan not only represents the practice of cultural

conventions, but the fixity of habitus is also subverted in performance. In this

section, I shall examine representations of female experience in Taiwan as one aspect

of post-colonial feminist discourse. In the terms of Bourdieu’s analysis of the

symbolic power of language and Henri Lefebvre’s concept of space as social

production, the Uhan Shii Theatre Group employs the symbolic power of theatrical

languages and space to subvert social hierarchies experienced in Taiwan (Bourdieu,

1991, pp. 163170; Lefebvre, 1991, pp. 3844). The company’s resistance to

patriarchy is demonstrated through their awareness of the symbolic power of local

languages and by reclaiming a space for women’s voices and performances in their

theatre.

The Uhan Shii Theatre Group is led by a female director and 80% of its

performers are community-based female elders. This means that female experience

has become one of the major subjects of their plays. Female elders not only express

their complex feelings and stories in drama, they also use theatre to demonstrate how

they survived different colonial and nationalist regimes and the patriarchy associated

with them by adopting strategies of both compliance and resistance. These female

performers seek to restore and disseminate Taiwanese female elders’ oral histories

through performance. This process uncovers stories previously hidden from view,

and thus inserts multiple ‘Her Stories’ into the previously unitary, masculine and

official ‘His story’. By disentangling the complex relations among colonialism,

nationalism, post-colonialism and feminism, their personal and collective stories

represent a significant aspect of post-colonial feminist discourse.

The representation of women’s experience of being silenced in the past to finding a

voice in the present subverts patriarchal traditions. In Echoes of Taiwan III the change

in women’ status is reflected in the transformation of the gestures and language of the

main female character, Li-Xiou. In the beginning, she is silent, submissive and

humiliated. With limited movement, she is cornered and confined in domestic chores

and space. She tolerates colonialism and complies with patriarchy in order to survive.

But after she has secured her economic independence in the 1980s, she begins

to defy patriarchal confinement. She becomes outspoken and even talks back to

her husband. Her gestures become expressive, and she moves actively to reclaim her

domestic space. In the end, she puts on make up and her best dress and leaves her

home to pursue her own enjoyment. The reversal of her physical and verbal language

signifies the possibility of the reversal of symbolic power between women and men in

Taiwan.

Henri Lefebvre has argued that representational spaces possess the power to

subvert and reshape the spatial structures of everyday life. Taiwanese women have

reshaped the fixed spatial power structures of gender relations in their performances.

In Echoes of Taiwan III , Li-Xiou makes her suppressed domestic experience public.

The dramatic representation of Li-Xiou’s change of gender politics offers a possible

model through which women might reclaim spaces previously denied to them.

Walking out of the home, Li-Xiou demonstrates that women can not only win an

equal place at home but they also can leave their confined domestic spaces and enter

the public space. Through performance, fixed divisions between gender relations are

dismantled and patriarchal power is redistributed into multiple agents and spaces.

Avoiding direct confrontation, Li-Xiou uses humorous remarks to satirise and

counter-act her husband’s rigidity and inability to adapt to the rapid changes evident

in Taiwanese society. By these actions, she demonstrates that Taiwanese women seek

equality and balance with men rather than dominating them or creating another

social hierarchy.

In Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here, premiered in 2000, a migration epic story of

Hakka (the second largest ethnic group in Taiwan) was delivered for the first time on

the Taiwanese stage in the Hakka language. The story spans the past to the present,

from the countryside to the metropolis, and the experience of Hakka women is the

main focus. These women use their Hakka dialect to tell their life stories and project

themselves into a public space, thereby countering their previous absence in public

and creating a new spatial reproduction. They employ the Hakka language and

singing to reclaim a space for Hakka women whose experiences and voices had been

previously marginalised by the double oppressions of KMT’s nationalism and

patriarchy. They share their personal stories of migration, showing how they make a

living in the metropolis and how they have moved from the confines of the domestic

place to the public space. Furthermore, their numerous tours (the production has

toured to remote Hakka villages for more than 50 performances and has travelled as

far as Wupertale, Germany in 2001) has meant that their stories have been seen on

various public platforms both in and out of Taiwan.

Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here reveals the hidden tradition of adopted

daughters in Hakka history for the first time on a Taiwanese stage. Some of the

female cast are ‘adopted daughters’ themselves, some of their mothers and sisters

were ‘adopted daughters’ who were given to another family in exchange for their

labour.6 Sharing collective memories of this exploitative system of adoption helps

them to come to terms with their suffering. In turn, the performance enables them

to show the inner feelings of these exploited daughters through dramatic narratives

and singing. In the scene of ‘Wrapping the Wound for the Little Girl’, enacted by

an all-female cast, they pass a long white strip of cloth towards each other slowly

(see Figure 2). It occupies and involves the whole stage and symbolises a cleansing

meandering river. It represents a healing ritual to comfort their traumas. The healing

space sometimes extends beyond the stage and reaches the audience who may have

endured similar afflictions.7

The production also portrays how Hakka women break free from their domestic

constraints and economic dependency. Women start to make a living to support their

families by tailoring or selling merchandise, and this is shown theatrically in Jyu-Ing’s

and Yu-Ching’s stories, both of whom are self-reliant Hakka mothers and career

women in real life. They either walk out of their domestic space and create their own

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan 83

career in the public domain or transform their domestic space into their workplace.

In contrast with the confinement, financial worries, suppression and anger that Jyu-

Ing had to put up with at home, she dances with her customers, using her tapemeasure

and mannequin to celebrate the economic independence she has gained by

transforming her home into a tailor’s studio.

In the last scene, the circling parade ‘Opening up the Bundle of Memory’, projects

the Hakka women’s memories into the auditorium (see Figure 3). Each woman

opens a blue bundle, which traditional Hakka people wrap up and carry around their

shoulders when they embark upon a faraway journey, and she shares her most

treasured memory with the audience. Xiou-Ching’s memory is a family photograph

in which her mother holds her tight and loves her dearly; Jyu-Ing’s blue bundle

contains her diary which accompanies her migration journey from village to city.

One after another, they circle around the auditorium and pass on the blue bundles

to children as passing on their Hakka heritage. The procession encompasses the

space with their memories of migration and projects them into their prospective

futures. This play has toured around the metropolis and remote Hakka towns

twice in the past five years with the intention of re-inscribing Taiwanese history

with Hakka women’s oral histories and re-affirming their identities through theatre

practice.

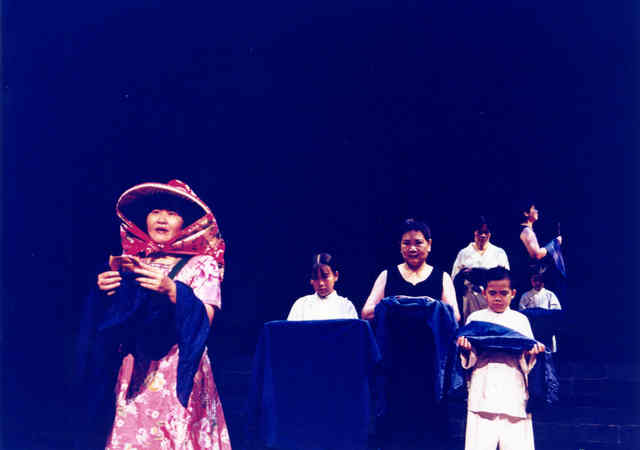

Figure 2. Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here (2000). This photograph captures the moment when

all the female cast work together to pass on the long white strip to wrap up the symbolic wounds

which scared the young adopted daughter as a healing ritual on stage. They are all dressed in the

renovated form of traditional Hakka female costumes, noted for their floral patterns. Courtesy of

the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

These examples illustrate how the Uhan Shii Theatre Group not only presents the

traditions of Taiwanese culture, but also subverts them by new representations of

contemporary female experience. The company presents how Taiwanese women

have dismantled fixed gender relations and destabilised patriarchy in ways that are

different from their feminist counterparts in Western cultures. The presentation of

the Taiwanese stories performed by the women themselves also subverts the

‘orientalist’ imagination about Asian women and challenges passive stereotypes

with which they are sometimes associated. Although the director Peng Ya-Ling,

never stresses their political aim as a ‘feminist group’ (Wang, 2004), the process of

women acting their own stories is part of a continual process of striving towards

social justice and gender equality. Through these cultural and theatrical strategies the

company intends to transcend binarism and open multiple choices and spaces for

different voices in Taiwan.

Notes

1. KMT is the leading nationalist party, led by Chang Kai-Shek, lost the civil war with

Communist China in 1947 and retreated to Taiwan. It built a settler-state in Taiwan

immediately after the Japanese returned Taiwan to Chang-Kai-Shek’s nationalist regime

and became the sole authoritarian and autocratic political party in Taiwan until 2000

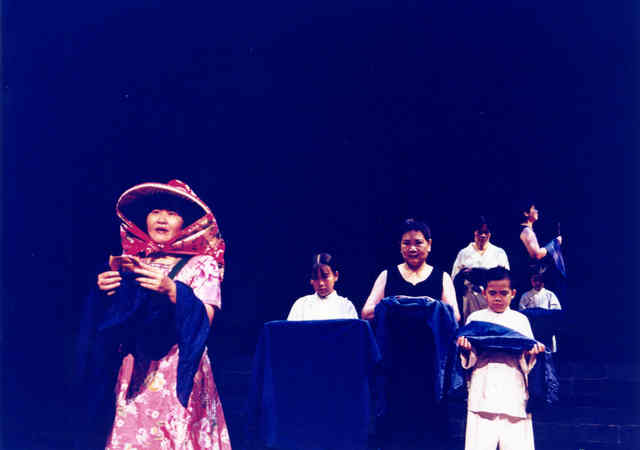

Figure 3. Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here (2000). This photo juxtaposes several scenes when the

elder female characters open up their blue bundles accordingly, share their most treasured memories

in migration, and pass them on to the younger Hakka generation. Courtesy of the Uhan Shii

Theatre Group

when the opposition party, Democratic Progress Party, won the presidential election for

the first time.

2. After the Democratic Progressive Party, which is mainly constituted of Holo people in

Taiwan, won the presidential election in 2000, the Holo, the largest ethnic group in Taiwan,

has become the dominant ethnic group. They tend to promote the formerly suppressed Holo

culture as the representative and leading Taiwanese culture and consequently marginalise

the previously privileged ‘mainlander group’ in nationalist rule as a cultural counterreaction.

3. The actor, Tsai Yi-Shan, was a retired film projector in real life and has now passed away.

4. Jacqueline Lo criticises in her poignant essay, ‘Beyond happy hybirdity: performing

AsianAustralian identity’: ‘Hybridity is not therefore perceived as a natural outcome but

rather as a form of political intervention . . .’. She also points to ‘happy hybridity’ as ‘the most

pernicious form of hybridity . . . found in eclectic postmodernism which the term is emptied

of all its specific histories and politics to denote instead of a concept of unbound culture’

(Lo, 2005, pp. 12).

5. Circular blocking is a typical, customary and stylised movement pattern in Chinese Opera.

Whenever a new character appears or exits the stage, he or she will make a circular

movement to give a clear demonstration of his or her distinctive character with stylised

postures and gestures. The circular movement also creates a constantly unbroken line

between movements on stage and secures a harmonious and smooth aesthetic quality in

Chinese traditional theatre. The circular movement is often used in dance and singing

sequences to deliver a continuous and flowing sense of beauty and momentum in traditional

Chinese Opera.

6. ‘Adopted daughters’ is one of the pervasive and common folk customs in Taiwan before

1970s. The main purpose of this custom was to lessen the financial burden of the traditional

Chinese big families, who consider daughters inferior to sons and thus they are considered to

be extraneous and to belong to their husbands’ families after they are married. It is

considered common to give away one’s daughters as other families’ ‘adopted daughters’ in

exchange for money and to help with the heavy labours of the adopted family if the original

family has too many daughters and is in severe poverty. Some of the daughters are bought in

order to become the future wives of their adopted family’s young sons. Often they are

physically and emotionally exploited when they were bereft from their kinship and used

extensively as child labour in the domestic setting.

7. According to my observations and interviews of the audience when I followed their tour

around some remote Hakka villages, I witnessed many female audience members shedding

tears when they saw the healing scene on stage happen for adopted daughters. In Guan-Xi,

the remote northern Hakka village in Taiwan, there were three female audience members

interviewed by me evidencing that they were comforted by the performance in different

degrees. They said that they felt they were more or less relieved by the secrets they buried

deep in their hearts as adopted daughters when they saw that their experience was shared by

so many other women and they seem to have mourned together in the performance for

themselves as well as for those sitting in the auditorium.

Notes on contributor

Wan-Jung Wang, born in Taiwan, is a theatre director, teacher and scholar. Having

published three books about theatre in Chinese: Peter Brook, With wings I fly

across dark nights and Stage vision, she is currently researching Reminiscence

Theatre at Royal Holloway, University of London as a PhD student.

References

Agnew, J., Mitchell, K. & Toal, G. (Eds) (2003) A companion to political geography (Malden, MA

and Oxford, Blackwell Publishers).

Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a theory of practice (R. Nice, Trans.) (Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press).

Bourdieu, P. (1991) Language & symbolic power (G. Matthew & R. Adamson, Trans.) (Cambridge,

Polity Press).

Connerton, P. (1989) How societies remember (Cambridge and New York, Cambridge University

Press).

Halbwachs, M. (1950) The collective memory (F. J. & V. Y. Ditter, Trans.) (London, Harper

Colophone Books).

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.) (Oxford, Blackwell).

Lo, J. (2005) Beyond happy hybridity: performing AsianAustralian identities . Available online at:

http://dlibrary.acu.edu.au/research/adsa/Lo.htm (accessed 5 August 2005), pp. 120.

Peng, Y.-L. (1995) DVDs of Echoes of Taiwan IIIXX of Uhan Shii Theatre Group in Taiwan (Taipei,

Uhan Shii Theatre Group).

Wang, W.-J. (2004) 12 interviews with the Director Peng Ya-Ling about Uhan Shii Theatre

Group’s methods and process in rehearsal, September 2003January 2004, Taipei.

(Wan-Jung Wang,〈The subversive practices of reminiscence theatre in Taiwan〉。《Research in Drama Education》Vol.11,No.1,February 2006,pp.77-87)

The subversive practices of reminiscence

theatre in Taiwan

Wan-Jung Wang*

Royal Holloway, University of London, UK

Founded in 1995, the Taiwanese Uhan Shii Theatre Group has created 12 distinctive reminiscence theatre productions and has performed locally in Taiwan as well as globally around the world. The company has developed its own theatrical aesthetics of memory, and their work not only represents the traditions of Taiwanese culture and habitus, but it also subverts its conventions. In this paper I will examine how the aesthetics of production represents Taiwanese cultural habitus and how their representation of female experience subverts orthodox cultural expectations and traditional gender roles associated with them.

The background and context of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

Taiwan has been ruled by different political regimes, undergoing colonisation by Japan and ‘re-colonisation’ by the Kuomingtang nationalists (shortened to KMT)1 immediately after the Japanese occupation in the twentieth century. Culturally and historically, Taiwan has been influenced by Chinese and Japanese imperialism as well as ‘modernised’ by Western neo-colonialism, and the hybrid culture of Taiwan indicates this post-coloniality. It was only after the lifting of Martial Law in 1987 that the Taiwanese began to reconstruct their own multiple histories and, as part of the process of decolonisation, started to renegotiate a more secure sense of their own identities. The Uhan Shii Theatre Group was founded in this emerging movement of cultural decolonisation in the 1990s.

The director of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group, Peng Ya-Ling, was an active theatre practitioner in the experimental theatre movement in Taiwan in the 1980s, where she adapted Western avant-garde theatre forms developed during the 1960s. Later, she went to London to attend the London School of Movement and Mime, and received rigorous training in Etienne Decroux’s form of corporeal mime. Although her performance was often praised by her British teacher as ‘uniquely Taiwanese’, she was unaware of this quality in her work at the time. When she returned to Taiwan in 1990s, she embarked upon a personal journey to seek her ‘uniquely Taiwanese’

*Department of Drama and Theatre, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey

TW20 0EX, UK. Email: w.c.wang@rhul.ac.uk

ISSN 1356-9783 (print)/ISSN 1470-112X (online)/06/010077-11

# 2006 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/13569780500437754

qualities. Her personal journey collided with a collective quest for cultural identity on

the island. By interviewing traditional performing artists and community-based

elders, she started to re-learn her own culture and traditions. These interviews

motivated the foundation of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group.

The Uhan Shii Theatre Group is the first Taiwanese theatre company exclusively

dedicated to the performance of the oral histories of community-based elders. By

recovering and performing their buried memories, the company reconstructs

Taiwanese historicised identity and, in the process, reaffirms it. The elder

performers, who had never before undergone any professional theatre training,

perform their life stories in collaboration with Peng Ya-Ling, the director. Reclaiming

a sense of their own post-colonial subjectivity is a shared goal for Uhan Shii’s director

and its elderly performers, who are differently marginalised according to gender,

ethnicity, and class groupings. In the following section, I will demonstrate how the

aesthetics of production presents and reclaims a specifically Taiwanese cultural

identity.

Aesthetics of production

Places are often inscribed by people’s memories and interpretations. Conversely,

people are also inscribed by the places in which they have dwelt. The interrelationship

between people and places is a process of inter-inscription and is constantly

changing according to people’s different needs at different times (Agnew et al. , 2003,

pp. 290297). Places are inscribed upon the elders’ bodies with cultural meanings

which derive from their social experiences. Pierre Bourdieu described the significance

of such physical imprints as ‘social habitus’, and sociologists Halbwachs and

Connerton have stressed the importance of the body in producing and reproducing

cultural remembrances (Halbwachs, 1950, pp. 7884; Bourdieu, 1977, pp. 7887;

Connerton, 1989, pp. 58, 88). This combination of the social and cultural practices

inscribed on the bodies might be described as a ‘cultural habitus’, a term I am using

to suggest the ways in which Taiwanese elders in the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

demonstrated their neglected and colonised cultures in performance.

On stage, the elders’ physical presence is visible to the audience as they tell their

stories and means that reminiscence theatre exhibits the historical sedimentation of

places upon bodies. In the Uhan Shii Theatre Group, Taiwanese cultural habitus is

presented by performative elements such as the elders’ dialect, singing, gestures,

postures and movement as well as the director’s mise en scene. The social habitus of

Taiwan is presented by the individual elders’ habitual gestures and postures which

derive from their social encounters in Taiwan.

The aesthetics of production evident in the company’s work reflects the influences

of the cultural habitus of Taiwan in two ways. One is concerned with looking for its

‘roots’ and the other is related to the ‘routes’ Taiwanese people have travelled and

their encounters with other cultures. Firstly, ‘looking for roots’ suggests the quest to

re-establish the subjectivity of the previously disfranchised and oppressed Taiwanese

people. The company deliberately recovers histories and languages of ethnic minority

groups such as Hakka and Holo who have been suppressed in the past, and those

from the currently marginalised ‘mainlander group’ in Taiwan.2 By performing

stories in their own dialects, these performers are offered the chance to restore

subjectivities that have been exploited by different dominating political regimes.

In 1995, the Uhan Shii Theatre Group started to devise a series of productions

called Echoes of Taiwan based upon the oral history accounts of Taiwanese

community-based elders. These productions established critical acclaim for their

theatrical reflection of Taiwanese cultural identities. In the production Echoes of

Taiwan III*/The Story of Taiwanese Men premiered in 1998, the Uhan Shii Theatre

Group demonstrates the cultural hybridity of Taiwanese men and women under

Japanese colonialism and KMT’s nationalism. The production also reflects the

influences of both Western and Chinese theatre cultures on the director Peng

Ya-Ling. This mirrors the two directions of Taiwanese cultural habitus: the roots, by

recovering histories hidden during the colonial and nationalist periods; and the

routes, by renovatingWestern and Chinese theatre cultures with a renewed vision. By

synchronising the influences of routes and roots, the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

reflects the complexity of contemporary Taiwanese culture.

In the first scene of Echoes III , the ritual of a Taiwanese man taking a bath

demonstrates the imprint of Japanese imperialism through a series of movements.

Portrayed by a retired merchant, Wu Wuen-Cheng, the man sits upright and

motionless with one arm straight up whilst his wife rubs his back silently. The

commanding and unyielding posture of the patriarchal man and the submissive

posture of a subservient and obedient wife reflect the imprint of Japanese colonialism

on Taiwanese culture. In contrast to the dominating position in his domestic life, in

public the Taiwanese man kneels down and bows in front of a Japanese soldier to ask

forgiveness for smuggling pork for his family. These two images mirror the complex

imprint of Japanese colonialism on elderly Taiwanese men. He both enacts Japanese

patriarchal postures at home and succumbs to an inferior position as the colonised in

public. By contrast, Taiwanese women are doubly oppressed by complying with both

colonialism and patriarchy and diminished into the role of silent submission. The

humiliation inscribed upon the wife is shown vividly in another scene when she serves

the tea respectfully for her husband and persistently extends her hand to ask money

from him, but in vain.

After Japanese colonialism, the KMT nationalists also left a legacy of suffering and

restraint on the Taiwanese people. That means that when the KMT nationalists

practised stringent political and military rule in Taiwan, they left physical imprints of

suppression on Taiwanese people. This point is demonstrated in the second part of

the Uhan Shii Theatre Group’s production of Echoes of Taiwan III . The character,

Tsai Yi-Shan’s father, was almost beaten to death in the period of ‘White Terror’

when the KMT crushed opposition to its police state. His crime was to ask KMT

soldiers to return his sheep which had been taken by force.3 Seeing his badly

wounded father, his mother’s creaking scream and cry resonates on stage. The image

of his mother wrapping his father haunted him for years and was made into an

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan 79

unforgettable stage picture (see Figure 1). Consecutively, the hushed gestures

exchanged between the two men crouching with their backs on small stools and their

image bound by the long white strips of cloth hanging from the ceiling, reflect the

physical and psychological restraints experienced under nationalist rule.

An alternative direction of Taiwanese cultural habitus is manifested in the

director’s travelling ‘routes’ from the West back to Taiwan. Through exploring

indigenous cultures, Peng Ya-Ling counter-balances the Westernisation and neocolonialism

that permeated the cultural scene of Taiwan in the 1980s. Furthermore,

her ‘unique Taiwanese’ quality is especially reflected in the hybridity of her acting

training and directing style. It is fused with indigenous Taiwanese theatre aesthetics,

Chinese traditional theatre concepts and Western experimental theatre forms.

Nevertheless, this hybridity reflected in her theatre works also contains a strong

awareness of the need to seek and sustain her own cultural subjectivity. This is a kind

of ‘critical hybridity’ rather than the ‘happy hybridity’ that Jacquelin Lo describes.4

Peng’s creative and critical synchronisation of artistic styles from different theatrical

traditions creates a new artistic style of her own. This is a distinctive example of the

hybridity of Taiwanese culture.

In her mise en scene, Peng Ya-Ling employs circular rather than linear blocking

which resonates with Chinese traditional theatre aesthetics.5 An example could be

drawn from ‘the lantern parade’ scene in which Taiwanese and Japanese children

circle the stage to parade their lanterns on the occasion of the Lantern Festival in

Figure 1. Echoes of Taiwan III*/The Story of Taiwanese Men in 1999, the scene demonstrates that

Tsai Yi-Shan recalls how he watched the sheep when he was a child as well as how his mother

wrapped up the wounds for his father, who is beaten by KMT nationalists at the far back of this

picture, as his life-long haunting image. Courtesy of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

Echoes of Taiwan III . In her choice of narrative strategy, she combines storytelling

directly addressed to the audience and lyrical singing that expresses the inner feelings

of a character. This is typical of the Chinese opera style, and is well-illustrated in the

soliloquies and Japanese singing in Echoes of Taiwan III . In the tender singing of

Japanese songs, the elderly man and woman express their ambivalent and suppressed

feelings towards Japanese colonial rule combined with love and hate, adoration and a

sense of inferiority. In the same production, the symbolic use of props such as stools

to represent sheep recalls the property usage in Chinese theatre. In a game-playing

scene, for example, Wu Wuen-Cheng and Tsai Yi-Shan play a game of throwing

cards while they talk about the restriction of Chinese education under Japanese

colonial rule. They pause at the point when they begin to throw their cards as they

are fixed by their time; they freeze the moment of play as a perpetual moment of their

childhood to highlight this memory. This tableau-like effect resonates with Chinese

opera’s ‘Liang Xiang’, which is a highly stylised movement in Peking Opera; when a

character first appears on stage, he or she will hold their characteristic posture and

gesture with a certain special tempo of music for a moment on stage in order to stress

their distinguishing characteristic.

The trademark of the Uhan Shii Theatre Group is the transformation of the

movements of daily life into stylised movements, thereby turning the ordinary into

the extraordinary. This derives from Chinese theatre aesthetics, in which daily

movements are deliberately stylised. The emphasis on physicalisation to reveal the

inner feelings comes from Ya-Ling’s meticulous training in the school of Etienne

Decroux in London. The best example of how this Western training has become

assimilated into her work is the scene of ‘pulling the white hair’ in Echoes of Taiwan

IV*/If You Had Called Me. The elders repeatedly pulling their white hair as a group

in slow motion symbolises the past that they wish to forget.

Peng Ya-Ling employs modern Western theatre aesthetics such as lighting, sound

effects and slide projection to create a ‘total’ theatre effect and to reinforce the

dramatic atmosphere. In the process of training the elders in acting, she has applied

Feldenkrais’ method to liberate the elders’ bodies from conditioned social bounds

and incorporated training in ‘psychodrama’ and ‘contact improvisation’ to unfix both

their physical and psychological blocks. In this collaborative process, Ya-Ling draws

upon improvisation techniques to develop scripts with the elders in the rehearsal.

The ritualistic slow motion movement, shown in the scene of ‘wrapping the wounded

father’ in Echoes of Taiwan III , derives from the non-realism style that Ya-Ling was

exposed to in the 1980s’ experimental theatre movement adapted from the West in

Taiwan.

Based upon the above examples, Uhan Shii’s aesthetics of production demonstrate

the cultural inter-inscription of roots and routes in Taiwan and reflect the on-going

process of Taiwanese identity formation. The performances also offer the opportunity

for a triple reflexivity upon histories from the performer, the director and the

audience. Their dialogues with their complex personal and cultural histories

continue to shape the new and ever-changing identity of Taiwan.

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan 81

Taiwanese female experience presents and subverts the symbolic power

and space

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan not only represents the practice of cultural

conventions, but the fixity of habitus is also subverted in performance. In this

section, I shall examine representations of female experience in Taiwan as one aspect

of post-colonial feminist discourse. In the terms of Bourdieu’s analysis of the

symbolic power of language and Henri Lefebvre’s concept of space as social

production, the Uhan Shii Theatre Group employs the symbolic power of theatrical

languages and space to subvert social hierarchies experienced in Taiwan (Bourdieu,

1991, pp. 163170; Lefebvre, 1991, pp. 3844). The company’s resistance to

patriarchy is demonstrated through their awareness of the symbolic power of local

languages and by reclaiming a space for women’s voices and performances in their

theatre.

The Uhan Shii Theatre Group is led by a female director and 80% of its

performers are community-based female elders. This means that female experience

has become one of the major subjects of their plays. Female elders not only express

their complex feelings and stories in drama, they also use theatre to demonstrate how

they survived different colonial and nationalist regimes and the patriarchy associated

with them by adopting strategies of both compliance and resistance. These female

performers seek to restore and disseminate Taiwanese female elders’ oral histories

through performance. This process uncovers stories previously hidden from view,

and thus inserts multiple ‘Her Stories’ into the previously unitary, masculine and

official ‘His story’. By disentangling the complex relations among colonialism,

nationalism, post-colonialism and feminism, their personal and collective stories

represent a significant aspect of post-colonial feminist discourse.

The representation of women’s experience of being silenced in the past to finding a

voice in the present subverts patriarchal traditions. In Echoes of Taiwan III the change

in women’ status is reflected in the transformation of the gestures and language of the

main female character, Li-Xiou. In the beginning, she is silent, submissive and

humiliated. With limited movement, she is cornered and confined in domestic chores

and space. She tolerates colonialism and complies with patriarchy in order to survive.

But after she has secured her economic independence in the 1980s, she begins

to defy patriarchal confinement. She becomes outspoken and even talks back to

her husband. Her gestures become expressive, and she moves actively to reclaim her

domestic space. In the end, she puts on make up and her best dress and leaves her

home to pursue her own enjoyment. The reversal of her physical and verbal language

signifies the possibility of the reversal of symbolic power between women and men in

Taiwan.

Henri Lefebvre has argued that representational spaces possess the power to

subvert and reshape the spatial structures of everyday life. Taiwanese women have

reshaped the fixed spatial power structures of gender relations in their performances.

In Echoes of Taiwan III , Li-Xiou makes her suppressed domestic experience public.

The dramatic representation of Li-Xiou’s change of gender politics offers a possible

model through which women might reclaim spaces previously denied to them.

Walking out of the home, Li-Xiou demonstrates that women can not only win an

equal place at home but they also can leave their confined domestic spaces and enter

the public space. Through performance, fixed divisions between gender relations are

dismantled and patriarchal power is redistributed into multiple agents and spaces.

Avoiding direct confrontation, Li-Xiou uses humorous remarks to satirise and

counter-act her husband’s rigidity and inability to adapt to the rapid changes evident

in Taiwanese society. By these actions, she demonstrates that Taiwanese women seek

equality and balance with men rather than dominating them or creating another

social hierarchy.

In Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here, premiered in 2000, a migration epic story of

Hakka (the second largest ethnic group in Taiwan) was delivered for the first time on

the Taiwanese stage in the Hakka language. The story spans the past to the present,

from the countryside to the metropolis, and the experience of Hakka women is the

main focus. These women use their Hakka dialect to tell their life stories and project

themselves into a public space, thereby countering their previous absence in public

and creating a new spatial reproduction. They employ the Hakka language and

singing to reclaim a space for Hakka women whose experiences and voices had been

previously marginalised by the double oppressions of KMT’s nationalism and

patriarchy. They share their personal stories of migration, showing how they make a

living in the metropolis and how they have moved from the confines of the domestic

place to the public space. Furthermore, their numerous tours (the production has

toured to remote Hakka villages for more than 50 performances and has travelled as

far as Wupertale, Germany in 2001) has meant that their stories have been seen on

various public platforms both in and out of Taiwan.

Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here reveals the hidden tradition of adopted

daughters in Hakka history for the first time on a Taiwanese stage. Some of the

female cast are ‘adopted daughters’ themselves, some of their mothers and sisters

were ‘adopted daughters’ who were given to another family in exchange for their

labour.6 Sharing collective memories of this exploitative system of adoption helps

them to come to terms with their suffering. In turn, the performance enables them

to show the inner feelings of these exploited daughters through dramatic narratives

and singing. In the scene of ‘Wrapping the Wound for the Little Girl’, enacted by

an all-female cast, they pass a long white strip of cloth towards each other slowly

(see Figure 2). It occupies and involves the whole stage and symbolises a cleansing

meandering river. It represents a healing ritual to comfort their traumas. The healing

space sometimes extends beyond the stage and reaches the audience who may have

endured similar afflictions.7

The production also portrays how Hakka women break free from their domestic

constraints and economic dependency. Women start to make a living to support their

families by tailoring or selling merchandise, and this is shown theatrically in Jyu-Ing’s

and Yu-Ching’s stories, both of whom are self-reliant Hakka mothers and career

women in real life. They either walk out of their domestic space and create their own

Reminiscence theatre in Taiwan 83

career in the public domain or transform their domestic space into their workplace.

In contrast with the confinement, financial worries, suppression and anger that Jyu-

Ing had to put up with at home, she dances with her customers, using her tapemeasure

and mannequin to celebrate the economic independence she has gained by

transforming her home into a tailor’s studio.

In the last scene, the circling parade ‘Opening up the Bundle of Memory’, projects

the Hakka women’s memories into the auditorium (see Figure 3). Each woman

opens a blue bundle, which traditional Hakka people wrap up and carry around their

shoulders when they embark upon a faraway journey, and she shares her most

treasured memory with the audience. Xiou-Ching’s memory is a family photograph

in which her mother holds her tight and loves her dearly; Jyu-Ing’s blue bundle

contains her diary which accompanies her migration journey from village to city.

One after another, they circle around the auditorium and pass on the blue bundles

to children as passing on their Hakka heritage. The procession encompasses the

space with their memories of migration and projects them into their prospective

futures. This play has toured around the metropolis and remote Hakka towns

twice in the past five years with the intention of re-inscribing Taiwanese history

with Hakka women’s oral histories and re-affirming their identities through theatre

practice.

Figure 2. Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here (2000). This photograph captures the moment when

all the female cast work together to pass on the long white strip to wrap up the symbolic wounds

which scared the young adopted daughter as a healing ritual on stage. They are all dressed in the

renovated form of traditional Hakka female costumes, noted for their floral patterns. Courtesy of

the Uhan Shii Theatre Group

These examples illustrate how the Uhan Shii Theatre Group not only presents the

traditions of Taiwanese culture, but also subverts them by new representations of

contemporary female experience. The company presents how Taiwanese women

have dismantled fixed gender relations and destabilised patriarchy in ways that are

different from their feminist counterparts in Western cultures. The presentation of

the Taiwanese stories performed by the women themselves also subverts the

‘orientalist’ imagination about Asian women and challenges passive stereotypes

with which they are sometimes associated. Although the director Peng Ya-Ling,

never stresses their political aim as a ‘feminist group’ (Wang, 2004), the process of

women acting their own stories is part of a continual process of striving towards

social justice and gender equality. Through these cultural and theatrical strategies the

company intends to transcend binarism and open multiple choices and spaces for

different voices in Taiwan.

Notes

1. KMT is the leading nationalist party, led by Chang Kai-Shek, lost the civil war with

Communist China in 1947 and retreated to Taiwan. It built a settler-state in Taiwan

immediately after the Japanese returned Taiwan to Chang-Kai-Shek’s nationalist regime

and became the sole authoritarian and autocratic political party in Taiwan until 2000

Figure 3. Echoes of Taiwan VI*/We Are Here (2000). This photo juxtaposes several scenes when the

elder female characters open up their blue bundles accordingly, share their most treasured memories

in migration, and pass them on to the younger Hakka generation. Courtesy of the Uhan Shii

Theatre Group

when the opposition party, Democratic Progress Party, won the presidential election for

the first time.

2. After the Democratic Progressive Party, which is mainly constituted of Holo people in

Taiwan, won the presidential election in 2000, the Holo, the largest ethnic group in Taiwan,

has become the dominant ethnic group. They tend to promote the formerly suppressed Holo

culture as the representative and leading Taiwanese culture and consequently marginalise

the previously privileged ‘mainlander group’ in nationalist rule as a cultural counterreaction.

3. The actor, Tsai Yi-Shan, was a retired film projector in real life and has now passed away.

4. Jacqueline Lo criticises in her poignant essay, ‘Beyond happy hybirdity: performing

AsianAustralian identity’: ‘Hybridity is not therefore perceived as a natural outcome but

rather as a form of political intervention . . .’. She also points to ‘happy hybridity’ as ‘the most

pernicious form of hybridity . . . found in eclectic postmodernism which the term is emptied

of all its specific histories and politics to denote instead of a concept of unbound culture’

(Lo, 2005, pp. 12).

5. Circular blocking is a typical, customary and stylised movement pattern in Chinese Opera.

Whenever a new character appears or exits the stage, he or she will make a circular

movement to give a clear demonstration of his or her distinctive character with stylised

postures and gestures. The circular movement also creates a constantly unbroken line

between movements on stage and secures a harmonious and smooth aesthetic quality in

Chinese traditional theatre. The circular movement is often used in dance and singing

sequences to deliver a continuous and flowing sense of beauty and momentum in traditional

Chinese Opera.

6. ‘Adopted daughters’ is one of the pervasive and common folk customs in Taiwan before

1970s. The main purpose of this custom was to lessen the financial burden of the traditional

Chinese big families, who consider daughters inferior to sons and thus they are considered to

be extraneous and to belong to their husbands’ families after they are married. It is

considered common to give away one’s daughters as other families’ ‘adopted daughters’ in

exchange for money and to help with the heavy labours of the adopted family if the original

family has too many daughters and is in severe poverty. Some of the daughters are bought in

order to become the future wives of their adopted family’s young sons. Often they are

physically and emotionally exploited when they were bereft from their kinship and used

extensively as child labour in the domestic setting.

7. According to my observations and interviews of the audience when I followed their tour

around some remote Hakka villages, I witnessed many female audience members shedding

tears when they saw the healing scene on stage happen for adopted daughters. In Guan-Xi,

the remote northern Hakka village in Taiwan, there were three female audience members

interviewed by me evidencing that they were comforted by the performance in different

degrees. They said that they felt they were more or less relieved by the secrets they buried

deep in their hearts as adopted daughters when they saw that their experience was shared by

so many other women and they seem to have mourned together in the performance for

themselves as well as for those sitting in the auditorium.

Notes on contributor

Wan-Jung Wang, born in Taiwan, is a theatre director, teacher and scholar. Having

published three books about theatre in Chinese: Peter Brook, With wings I fly

across dark nights and Stage vision, she is currently researching Reminiscence

Theatre at Royal Holloway, University of London as a PhD student.

References

Agnew, J., Mitchell, K. & Toal, G. (Eds) (2003) A companion to political geography (Malden, MA

and Oxford, Blackwell Publishers).

Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a theory of practice (R. Nice, Trans.) (Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press).

Bourdieu, P. (1991) Language & symbolic power (G. Matthew & R. Adamson, Trans.) (Cambridge,

Polity Press).

Connerton, P. (1989) How societies remember (Cambridge and New York, Cambridge University

Press).

Halbwachs, M. (1950) The collective memory (F. J. & V. Y. Ditter, Trans.) (London, Harper

Colophone Books).

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.) (Oxford, Blackwell).

Lo, J. (2005) Beyond happy hybridity: performing AsianAustralian identities . Available online at:

http://dlibrary.acu.edu.au/research/adsa/Lo.htm (accessed 5 August 2005), pp. 120.

Peng, Y.-L. (1995) DVDs of Echoes of Taiwan IIIXX of Uhan Shii Theatre Group in Taiwan (Taipei,

Uhan Shii Theatre Group).

Wang, W.-J. (2004) 12 interviews with the Director Peng Ya-Ling about Uhan Shii Theatre

Group’s methods and process in rehearsal, September 2003January 2004, Taipei.

(Wan-Jung Wang,〈The subversive practices of reminiscence theatre in Taiwan〉。《Research in Drama Education》Vol.11,No.1,February 2006,pp.77-87)

全站熱搜

留言列表

留言列表